Newcastle United v Sunderland AFC – History Is Everything

An artists impression of the NUFC v SAFC game circa 1902 at St James Park

An artists impression of the NUFC v SAFC game circa 1902 at St James Park

It’s the game that everyone wants to see and it excites the football fan from the moment the fixture list comes out. It’s the one most likely to cause civil disorder and to have its roots in some facet of a country’s, city’s or region’s society and history. It is, of course, the football “derby” game.

From Argentina to Zambia, each country affiliated to FIFA – football’s governing body – will have a fixture or fixtures that provoke the reasonable and the unreasonable citizen into a feeling of mutual loathing for the opposition supporter who may be known or unknown to them, for the duration of the match or perhaps permanently. At times it defies belief and all rational norms.

Argentina has the famous Boca Juniors versus River Plate fixture, a game rooted in the poor–rich divide in Buenos Aires. In Glasgow, Scotland, there is the Rangers and Celtic match that has its roots in religious conflict.

In the northeast of England there is a football rivalry as intense as anywhere in the world, a rivalry that goes back as far as the English Civil War, nearly 400 years ago. It doesn’t just have a sporting background: it has an industrial and political one. Two communities collide. Society may have changed and the method of sorting out disputes and enmity may have altered, but, in its essence, this football rivalry is a continuation of a battle that commenced with Oliver Cromwell and King Charles I.

Needless to say, that rivalry is between Newcastle United FC and Sunderland AFC – the Tyne–Wear derby game.

In writing of this tale the matches themselves doesn’t do the story justice. Inevitably there are unpalatable events to be related that provide a context to the nature of the rivalry. However the white hot rivalry remains fact.

Facts, however, when it comes to the Geordies (Newcastle United) and the Mackems (Sunderland) are always arguable, a contradiction that cannot be explained. Even monumental defeats for one side or the other can easily be justified, to ensure that neither club is seen as weak in the face of the “enemy”. Neither team ever beats the other; it merely gains an upper hand that will be rectified the next time they meet.

For people who do not like football, or even for those who do, some of the events that surround this fixture provoke widespread disapproval. They have potentially far-reaching consequences for the local communities and individuals, making it imperative that authorities such as the police regard the games with heightened importance.

When the games are over, the games aren’t over – another contradiction. Go to towns such as Chester-le-Street in County Durham, South Shields, the City of Durham, and several additional locations, mainly near the border of Tyne and Wear and County Durham, and social disorder in the aftermath of the game is common and often expected, and the sound of police sirens can fill the air. Communities split 50/50, and when you add alcohol and throw in testosterone, you get an inevitable cocktail of violence.

What sets the Newcastle v Sunderland rivalry apart from other football derby games is that the two teams don’t even come from the same city. They are situated 12 miles apart. It might as well be a million miles, such are the differences in attitude between the two sets of fans.

Those that live within the Sunderland city boundaries have had their enmity towards Newcastle stoked by such events as the transfer of the seaside city into the newly created Tyne and Wear county in 1974, following the 1972 Local Government Act. This unpopular move saw Sunderland leave County Durham. Annoyance even extended to the building of the Tyne & Wear Metro public transport system in 1980, which initially served Tyneside but not Wearside – rightly or wrongly the people of Sunderland considered that they had contributed to it for 22 years through local taxes and received nothing in return. The facility was extended east towards the North Sea in 2002.

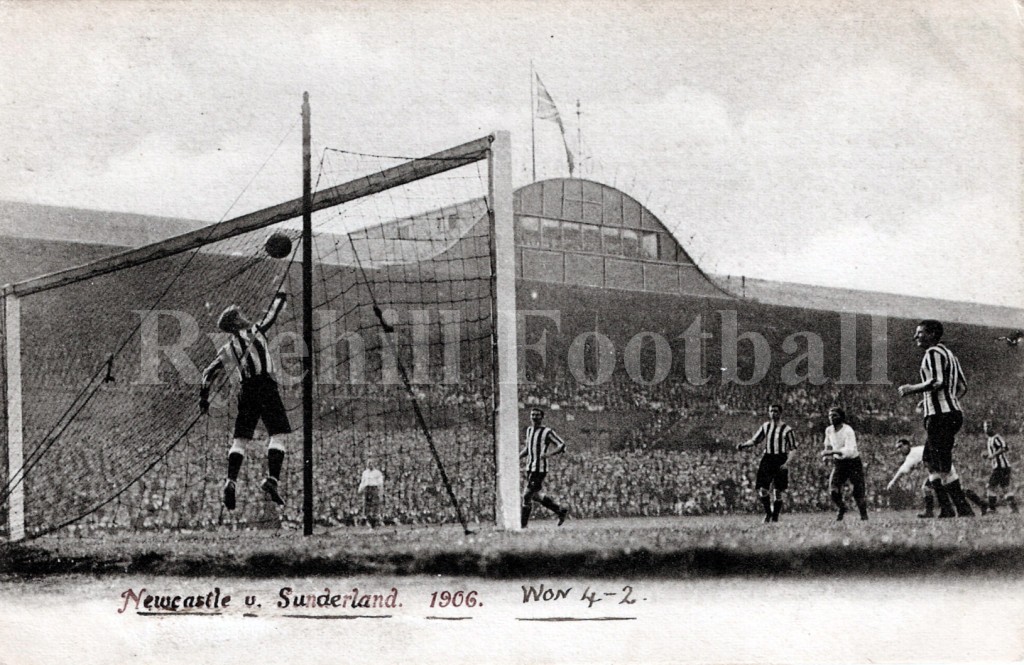

A Geordie win in 1906, prelude to humiliation for NUFC by Sunderland in 1909

The rivalry extends to absurdity, with some fans of Newcastle United reportedly refusing to eat bacon, due to its red-and-white colouring, whilst the popular breakfast cereal Sugar Puffs is still boycotted by many Sunderland fans due to the fact that the former Newcastle United manager Kevin Keegan was used in one of Kellogg’s more famous commercials 20 years ago. Don’t tell them about the honey, mummy, in Sunderland.

However, let’s not concentrate wholly on the social aspects of the fixture, critical though they are to understanding its place in northeast life and football folklore. The story of the Tyne–Wear derby also tells of marvellous football matches, sublime footballers, electric atmospheres that can only be cut with a very sharp knife and eras long forgotten. The fixture started in Victorian times and is still going strong in the 21st century.

It’s black and white (Newcastle United) versus red and white (Sunderland).

Sunderland AFC (SAFC) is the senior club, Newcastle United (NUFC) the junior but, as with a lot of tales in life, sometimes the pupil becomes the master, albeit temporarily. Remember, no one ever truly wins this fixture. What we have here is one big football match that has lasted, so far, for 130 years.

The story, however, starts in 1639.

THE BATTLE OF BOLDON HILL

The Bishops’ Wars, which took place in 1639 and 1640, were precursors to the English Civil wars, of which there were three. At the heart of the Bishops’ Wars was the intention of the then king, Charles I, to impose Anglican reforms on the Scottish Church, something that was rejected out of hand by the Scots. Angered by this, the king sent an expeditionary force northwards to bring the Scots to heel, but due to financial constraints and a lack of faith in his rabble army they returned to England without a shot being fired.

Despite being chastened by this, Charles I turned to parliament for support; however, the simmering rivalry between the monarchy and parliament was such that the latter rejected the king’s pleas for funds to build an army capable of mounting a proper challenge to the Scots. As a result Charles dismissed parliament and marched on Scotland – only to find, much to his surprise, that the English forces were routed by the Scots.

Although Charles I attempted to make peace with parliament, any trust between the parties evaporated on 4th January 1642 when the king’s men attempted to arrest five members of parliament. However, they were spirited away prior to the troop’s arrival. Charles then left London and raised the Royal Standard in Nottingham in August 1642, placing his troops under the command of the 3rd Earl of Essex. The scene was set for a civil war: Royalists v Parliamentarians.

Most of the country was neutral at the start of the conflict and, indeed, fighting men on each side amounted to only about 13,000. The Royalist support was centred around the north and west of England plus Wales. The Parliamentarians held the more affluent areas of the south and, critically, many of the ports.

The initial battles in the first English Civil War were fought in and around London, specifically Edgehill and Turnham Green. From there, conflict spread to engulf many other parts of the country.

In the northeast of England there was a growing animosity between the peoples of Sunderland and Newcastle. In order to keep the support of the richer Newcastle, Charles had consistently awarded the east of England coal trade rights to the merchants of that city. This effectively impoverished the people in Sunderland, who, as a result, sided with the Parliamentarians (also known as the Roundheads). Something had to give.

In 1643 the Parliamentarians enlisted the help of Scottish soldiers, known as Covenanters, in exchange for the Scots’ right to religious freedom, and an agreement called the Solemn League and Covenant was drawn up between the two parties. As a result, on 19th January 1644, the Army of the Covenant crossed the River Tweed and entered England under the command of the Earl of Leven. They headed south towards the Royalist stronghold of Newcastle, intent on taking it for parliament.

However, on 2nd February 1644, the Marquis of Newcastle, William Cavendish, beat them to it, and entered the city from the south with his army from Yorkshire, just hours before the arrival of the Covenanters. One day later the Earl of Leven’s request for the surrender of Newcastle was rejected, and a subsequent skirmish took place, with the Scottish forces capturing the outskirts of the city. On 6th February Scottish artillery landed in Blyth port but took two days to reach Newcastle, and on 8th February further skirmishes took place in and around Gateshead.

The Earl of Leven then took stock of the situation and bypassed Newcastle, crossing the Tyne at Ovingham, Bywell and Eltringham, and marching his troops towards the Parliamentary sympathetic town of Sunderland, where he could rest and plan tactics. The Covenanters were welcomed with open arms. On hearing this the Marquis of Newcastle (who died in 1676 and was subsequently buried at Westminster Abbey) left the city undefended and, together with his Royalist army, headed towards Sunderland, intent on routing the Covenanters.

At Penshaw Hill, south of Sunderland, the two armies were set to meet; however, the weather intervened, so Leven returned to Sunderland and the Marquis moved on to another Royalist stronghold – Durham.

In subsequent days the Scots took both South Shields and Chester-le-Street; the latter was a strategically important place from which a march to York, a bastion of monarchist support and the hub of the Marquis’ communication with the king, could commence.

Inevitably, a northeast conflict between the Royalist and Parliamentary forces would take place and, on 25th March 1644, the Battle of Boldon Hill was fought. Boldon Hill, for those who don’t know the northeast, lies between Newcastle and Sunderland, but nearer to the latter.

Although popular myth has it that the Newcastle forces were routed this wasn’t quite the case as the Scots were driven back to the safety of Sunderland by 4,000 of the Marquis’ troops and 3,300 Royalist cavalry under the command of Sir Charles Lucas (ironically the Marquis was widely regarded as the finest horseman in Europe at that time). However, the Marquis had a simple choice, continue the defence of Newcastle and lay siege to Sunderland or open up a second front by putting his efforts into securing York, a strategically more important location and one which some of the Covenanters were now marching towards. He chose York, situated in the county where most of his forces were from. However, the Covenanters subsequently took nearby Selby just days after Boldon Hill, before the Marquis could get there, and once he arrived in York, outnumbered and without support, an endgame was already being played.

By fleeing towards York the Marquis left the City of Newcastle open to conquest and thus the Parliamentarians came out of Sunderland and gained a significant victory. The battles of Stamford Bridge and then Marston Moor took place later that year, near York – utilizing 17,000 troops, the Roundheads conquered – which resulted in the Marquis of Newcastle humiliatingly fleeing abroad. He travelled to Hamburg, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Paris and then on to Antwerp, where due to his past friendship with people in the city, including the family of the Flemish baroque artist Anthony van Dyck, he settled for a while. The Royalists thus ceased to be a fighting force in the northeast of England.

Not only had Sunderland assisted the Parliamentarians in capturing Newcastle it had also contributed, albeit unwittingly, to the desertion of the Marquis.

In recognition of its loyal service to parliament Oliver Cromwell, himself an MP, transferred many of the coal licences from Newcastle to Sunderland.

However, the tale does not end there.

In 1660 what was known as the Restoration took place, effectively reviving the monarchy under King Charles II (and also allowing the Marquis of Newcastle to return to England). Many of the coal licences were given back to Newcastle. What made matters worse for Sunderland was that a local coal cartel, known as the Vend, emerged, and ensured that London received its supply from Newcastle.

However, the arrival of Arthur Mowbray in 1814 fatally undermined the Vend. His attempts to modernize the local Vane-Tempest collieries inspired the expansion of the northeast railway network to Sunderland, with a subsequent boom in trade that led, amongst other things, to Sunderland being recognized as the biggest shipbuilding town in the world.

Mowbray is acknowledged to this day with a green belt known as Mowbray Park, which is situated near Sunderland city centre.

For those who do not know the northeast of England perhaps an explanation is necessary. The region was exceptionally industrialized and, historically, has at its heart coal mining and shipbuilding. Both the River Tyne (Newcastle) and the River Wear (Sunderland) became crucial to the economic well-being of the region. It’s doubtful that any family whose roots belong in the northeast, does not have a member who at some point was either a coal miner for the National Coal Board (NCB) or a shipbuilder for firms such as Austin & Pickersgill (Wearside) or Swan Hunter (Tyneside).

Before we move on it is worth mentioning what appears to be a reported factual inaccuracy in the historical dispute between the two communities. It is often cited that they opposed each other during the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745, which led eventually to the Battle of Culloden. The confusion appears to have arisen due to the belief that the then Duke of Newcastle sided with the monarchy and the then Earl of Sunderland sided with the Stuarts (as represented by the person of Bonnie Prince Charlie). However, the Earl of Sunderland (a subsidiary title of the Duke of Marlborough) was not from Sunderland but from Wiltshire. Furthermore, there is no evidence to suggest that he ever supported the Jacobite cause.

Notwithstanding the confusion over the Jacobite Rebellion, as it stood Sunderland had fought two conflicts against Newcastle, one political and one industrial, and had eventually gained the upper hand in both. However, as we shall see in this enduring battle between the two cities (Sunderland became a city in 1992) victory remains temporary, and in any case Newcastle is widely – albeit arguably – now regarded as the region’s capital, so perhaps the latter has had the last laugh after all.

By the time Sunderland AFC was formed, the shipbuilding town that gave birth to it was booming. The formation of Newcastle United would come later and would partially owe its existence to cricket!

A third conflict between the two cities was about to begin and would be played out on a football field rather than a battlefield.

As we know, it still takes place today.