Robert Kyle (Manager) – 1 August 1905 to (15 March 1928) / 5 May 1928

(click for larger image)

|

Played |

Won |

Drawn |

Lost |

For |

Against |

|

|

League |

758 |

345 |

141 |

272 |

1367 |

1157 |

|

FA Cup |

59 |

26 |

14 |

19 |

106 |

73 |

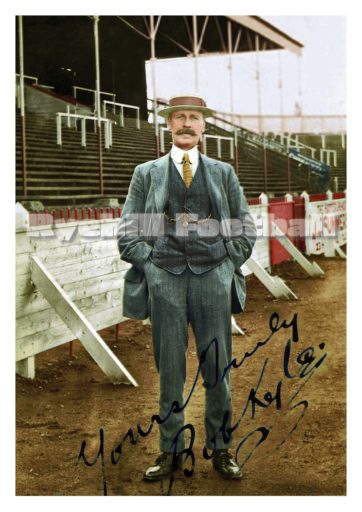

Above is Kyle standing in front of what I think is the Clock Stand circa 1912. It’s a quite marvellous image of the man who led Sunderland AFC longer than any other man in history. The image is scanned in such detail that you can make out the stripes on his trousers.

Prologue: The Man Who Stayed

Football history tends to be told through its visionaries and revolutionaries. Herbert Chapman at Arsenal, Matt Busby at Manchester United, Bill Shankly at Liverpool — men who built dynasties with fire and flair. Yet the game also belongs to quieter figures: men who shaped clubs not with bold gestures, but with persistence, endurance, and a steady hand on the tiller.

One such figure was Robert Hugh Kyle, the Belfast-born secretary-manager who guided Sunderland AFC from 1905 to 1928. Over nearly a quarter of a century, he managed 817 matches — still a record for the club. His reign delivered a First Division championship in 1913, an FA Cup Final appearance in the same year, and a post-war runners-up finish in 1923. More importantly, he carried Sunderland through years of financial difficulty, the upheaval of the First World War, and the volatile footballing world of the 1920s.

Kyle was not a touchline general, nor a tactical showman. He was a secretary in the Edwardian mould: quiet, methodical, a master of contracts and scouting. Yet his impact was profound. In an era when football clubs often lurched from one crisis to another, Kyle gave Sunderland something rare: stability.

Chapter 1: Belfast Beginnings

Kyle was born in Belfast, 16 December 1870, into a city where football was beginning to rival rugby as the game of choice for working men. By the 1890s, he had found his place not on the pitch but in the office, becoming club secretary at Belfast (Lisburn) Distillery.

Under his guidance, Distillery won three Irish League titles, two Irish Cups, a City Cup, three County Antrim Shields, and a Belfast Charity Cup. He became known for his calm efficiency and eye for players.

As a young man he played as a goalkeeper for the club, an amateur career that gave him a love for the game, but it was in administration that he found his calling.

There, Kyle established himself as an astute organiser. In Ireland, the secretary was often more influential than the coach, and Kyle excelled in this hybrid role. Newspapers soon recognised his ability. Ireland’s Saturday Night called him “one of the most capable secretaries in football.”

It was this reputation that caught the attention of Sunderland AFC across the Irish Sea; helped when his Distillery side defeated Sunderland in a friendly match during the 1903/04 campaign. However; Kyle was recommended to the club by fellow Irishman John McKenna who would become president of The Football League in 1917; and was the first manager of Liverpool FC.

By 1905, the Wearside club needed precisely the kind of calm, competent figure Kyle had become.

Chapter 2: Sunderland in 1905 — Crisis and Opportunity

Sunderland had been giants in the 1890s, earning the nickname the “Team of All Talents.” They won the league title three times in four seasons, and their thrilling football drew admiration across the land. But by 1905, glory had faded. Financial problems gnawed at the club. Results were inconsistent. Supporters were frustrated, and directors feared decline.

Into this turbulence stepped Robert Kyle. Appointed secretary-manager in August 1905, he arrived with little fanfare but considerable authority. The local press saw the wisdom of the choice. The Sunderland Echo & Shipping Gazette’s respected columnist “Argus” assured fans: “no man in football had a sounder knowledge of players and the game.” The Evening Telegraph echoed the sentiment: “Mr Kyle had the qualifications needed… in a short while the club was sailing in calmer waters.”

Kyle’s brief was clear: bring order, rebuild credibility, and restore Sunderland to strength.

Chapter 3: The Edwardian Rebuild

Kyle’s first years were about steady reconstruction. He trimmed costs, imposed financial discipline, and began assembling a squad capable of competing at the top. His recruitment was pragmatic rather than spectacular, but effective.

By the 1908–09 season, Sunderland finished third in Division One, their highest placing in years. The revival was under way. Crowds returned to Roker Park, filling the terraces with the noise of flat-capped shipbuilders and miners, eager for a glimpse of the club’s resurgence.

On Saturdays, the streets of Monkwearmouth were thick with fans marching to the ground. Vendors sold roasted chestnuts and match programmes, while brass bands played before kick-off. The stands trembled with choruses of “Ha’way the Lads.” Kyle, quietly observing from the touchline or directors’ box, was no showman. But his presence was felt in the orderliness of the club, in the steady rise of results.

Chapter 4: The Masterpiece of 1912–13

The pinnacle of Kyle’s work came in the 1912–13 season, still considered Sunderland’s greatest campaign before the First World War.

The Squad of Stars

Kyle’s genius lay in assembling a side that balanced flair with function. Among its stars were:

- Charlie Buchan, the brilliant inside-forward and future England captain.

- Jackie Mordue, a winger of devastating speed and accuracy.

- George Holley, a striker of ruthless finishing ability.

- Leigh Richmond Roose, the eccentric, beloved Welsh goalkeeper whose antics — leaping into crowds, charming spectators — made him a cult figure.

The League Title

Sunderland stormed the First Division, winning 25 matches and scoring 83 goals. Their attack was the envy of England, and their defence, marshalled with calm, rarely faltered. They finished champions with swagger, the pride of Wearside restored.

One report described their football as “unrelenting, a storm upon the citadel of every opponent.” Shipbuilders and miners filled Roker Park to bursting, their cheers rolling like waves across the North Sea.

The FA Cup Final

The league triumph was followed by a march to the FA Cup Final at Crystal Palace on 19 April 1913. For Sunderland, it was a day of pilgrimage. Special trains carried thousands south from Wearside, carriages crammed with red-and-white clad fans waving rosettes and scarves. They sang songs in dialect, pounded train tables in rhythm, and arrived in London determined to outshout Aston Villa.

The crowd of 121,919 was the largest ever to watch a football match in England. Under the grey spring skies, Sunderland battled fiercely. Charlie Buchan commanded play with his usual authority, dictating tempo like a general. But fate was cruel. Villa scored once and held firm. Sunderland’s dream of the double vanished in a 1–0 defeat.

Yet even in loss, pride endured. Sunderland had won the league and reached the Cup Final — an achievement unmatched in their history to that point.

Chapter 5: Charlie Buchan — Kyle’s General

No account of Kyle’s Sunderland is complete without Charlie Buchan, the man who defined his team.

Signed from Leyton in 1911 for £1,250, Buchan was not an obvious star. But Kyle’s eye for talent proved sound. He saw in Buchan an intelligent inside-forward, a man who played with his head as much as his boots.

In the 1912–13 season, Buchan was magnificent. He scored 30 league goals, orchestrated Sunderland’s attack, and became the idol of Roker Park. Fans adored his upright running style, his calm passes, and his knack for goals at crucial moments.

The First World War interrupted his career, but it also revealed the depth of respect between player and manager. In 1917, serving on the Western Front, Buchan wrote directly to Kyle from the trenches. In his letter he offered greetings from the battlefield, reassured Kyle of his well-being, and spoke of his longing for football and for Sunderland.

The image is striking: a soldier, mud-stained and weary, still thinking of his club, still writing to his manager as if Roker Park remained just around the corner. It speaks volumes about Kyle’s quiet authority and about the bond he forged with his players. Kyle was not merely their employer; he was a figure of stability, someone they trusted even amidst the chaos of war.

The FA Cup Final defeat was a personal heartbreak for Buchan, but it cemented his reputation as one of the best in England. Later capped for his country and eventually joining Arsenal, Buchan would end his career as one of football’s great figures — journalist, broadcaster, and founder of Charles Buchan’s Football Monthly, the iconic magazine.

Yet he always looked back on Sunderland under Kyle as his finest years. “At Sunderland I grew as a footballer, and those were the finest years of my career,” Buchan later reflected.

For Kyle, Buchan was indispensable — the general on the field who translated his steady leadership into action. Together, manager and player delivered Sunderland’s greatest triumph.

Chapter 6: Clouds of War

The triumph of 1913 came on the eve of catastrophe. The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 stopped football after one final season. Sunderland’s squad, like every other, was torn apart by enlistments.

Leigh Richmond Roose, the charismatic former goalkeeper, was killed on the Somme in 1916. Others returned scarred, physically or mentally.

Kyle remained at Roker Park, managing wartime competitions and keeping the club alive. His steady stewardship ensured Sunderland would have something to return to when peace came.

Chapter 7: Picking Up the Pieces

When the Football League resumed in 1919, Sunderland — like Britain — was a changed place. Crowds poured back into stadiums, hungry for diversion after the horrors of war. But Kyle’s squad was diminished, and rebuilding was slow.

Still, by 1922–23, he had crafted another contender. Sunderland finished second in Division One, behind only Liverpool. It was his last great flourish, proof that even after war, Kyle could build competitive sides.

Chapter 8: The Long Goodbye

The mid-1920s were years of stability without glory. Sunderland hovered in mid-table, occasionally threatening but never conquering. Yet they remained in the First Division, a fact not to be underestimated in such volatile years.

By 1928, Kyle was 57, his hair grey, his frame stooped. On 15 March 1928, he announced his retirement after 23 years. The board presented him with a £1,000 testimonial cheque — a grand gesture in the age.

His farewell coincided with a relegation battle. In his absence, trainer Billy Williams took charge for the final match, he would also leave at the end of the season having been with the club since 1897; a tense derby at Middlesbrough. Sunderland triumphed 3–0, securing safety. It was the perfect send-off: survival once more, the hallmark of Kyle’s stewardship.

Chapter 9: Legacy

Robert Hugh Kyle’s achievements are unmatched:

- 817 matches in charge (a Sunderland record).

- League champions, 1912–13.

- FA Cup runners-up, 1913.

- League runners-up, 1922–23.

- The only Irish manager ever to win the English league title.

But his true legacy lies not only in silverware but in endurance. He gave Sunderland stability through tumultuous decades, delivered their last pre-war title, and left them safe in the First Division.

The press summed him up best. The Telegraph wrote: “An official who was generally regarded as highly capable, and who has undoubtedly rendered excellent service to the club.”

Epilogue: The Quiet Titan

Kyle was no Chapman, no Shankly. He was quieter, subtler, less inclined to seek fame. Yet he was no less important to Sunderland. He built their greatest team, carried them through war, and ensured their survival in lean times.

Robert Hugh Kyle lived quietly after retirement. He resided at The Westlands in Sunderland, with his wife. On 17 February 1941, he died at Sunderland Royal Infirmary, aged 70.

His funeral took place at North Bridge Street Presbyterian Church, fitting for a Belfast Presbyterian transplanted to Wearside, and he was cremated at Newcastle upon Tyne.

The Sunderland Echo’s “Argus” had judged him accurately back in 1905: “no man in football had a sounder knowledge of players and the game.”

At Roker Park, they called him the secretary. History should remember him as what he truly was: the quiet titan of Sunderland AFC.