Sunderland AFC; The War Years

Raich Carter scores at Roker Park in the 1942 War Cup final against Wolverhampton Wanderers

The 1938-39 season was played against the backdrop of peace in our time, with some players joining the Territorial Army and the Football Association and Football League discussing plans for the game in the event of war being declared.

The 1938-39 season was played against the backdrop of peace in our time, with some players joining the Territorial Army and the Football Association and Football League discussing plans for the game in the event of war being declared.

For football, this was against the background of the events during the First War when the professional game attracted considerable and at times savage criticism from the press and some sections of the public for continuing a League programme to the end of the 1914-15 season. Many in charge of the game still remembered these events, and alongside a determination to maintain business as usual was the desire to do your bit for your country.

This was, perhaps inevitably, not always achieved. The sheer anger and frustration of seamen fishing bodies out of the Channel after Dunkirk whilst hearing a football match and the roar of the crowd on their radio can easily be understood. At the same time football as an escape and a relaxation from the war effort was, though perhaps with some hindsight, an important factor.

Sunderland AFC, together with its players and supporters, all played their own individual and collective part during World War Two, and this story is told not as if the war and its suffering and heroism did not happen, but from the standpoint that football was, and would remain, part of the community.

Five days before the start of the ill-fated 1939-40 season, the FA waived the rule which prevented members of the forces from being registered as professional footballers. Sunderland’s first two League games were at home, and a crowd of 21,859 saw a 3-0 win over Derby on the opening day with Carter scoring twice. After a disappointing midweek defeat by Huddersfield the team travelled to London on the Friday, in the company of reservists on the train and against the background of the ultimatum given to Hitler.

The next day saw the invasion of Poland, though the Home Office gave permission for that day’s games to take place. Sunderland’s game at Arsenal was delayed until 5pm because of the evacuation scheme and a small crowd of 17,141 saw Ted Drake score four for the Gunners in a 5-2 win. There could have been few of those present who could concentrate on the game in progress. Certainly Raich Carter said that he had little recollection of the game itself.

War was declared on the Sunday, and the Sunderland players and management heard the news in their London hotel, and endured the first air-raid warning of the war there. They travelled back to Sunderland, and the next week the instruction came from the Football League to cancel all League fixtures and suspend players’ contracts.

This effectively threw all players out of work, and having considered this and a Home Office regulation – soon afterwards amended – banning the assembly of crowds, the Sunderland directors decided to close the club down and take no part in the regional competitions starting to be discussed in the light of a 50-mile restriction on travel.

The club therefore, and as had happened during the First War, effectively went into limbo for the next 6 months. As for the players, they had to find themselves employment quickly – there was no National Insurance or dole money. Although enlistment in the forces was clearly the preferred option for many, this took time and temporary jobs were a must. Len Shackleton – released by Arsenal the previous April – found a job in a paper mill at Dartford, whilst Alex Hall returned to Scotland to play for Hibs in the newly constituted Scottish Eastern Division and Jimmy Russell worked in the shipyards.

Raich Carter summed the position up well when he admitted he had made a mistake in joining the Auxiliary Fire Service immediately rather than wait for a position in the armed forces, and suffered taunts and slurs for allegedly dodging the call-up (he was to join the RAF two years later). Len Duns joined the Royal Artillery, whilst other Sunderland players went into work in the shipyards and mines. Most retained their connection with the game, albeit with a variety of clubs.

But to return to 1940. Sunderland had, doubtless, heeded the words of a police chief quoted as saying football is the best teetotal agency we can produce for the worker and others left behind at home. If there is no football each week our cells will be full because the young men of today will have nowhere to go and will fall into mischief.

The club therefore reopened for business and entered the League War Cup in 1940, beating Darlington (4-3) and Leeds (1-0) to reach the Third Round before going out 2-3 to eventual finalists Blackburn. The decision was however taken to revert to friendly matches only for the next season; several matches were played with the gate receipts generally going to the War Fund.

The fact that Sunderland was at this time enduring heavy air raids, coupled with the proximity of Roker Park to the shipyards, was a factor in the decision not to enter a regular competition. By comparison with other League grounds however, despite its situation Roker Park escaped relatively unscathed during the War. During one raid in 1943 the old clubhouse at the corner of the Roker End was destroyed whilst one of a stick of bombs which fell a few weeks early killed a special constable patrolling outside the ground, another bomb leaving a crater in the pitch.

Crowds were, initially, severely limited by the authorities concerned about the ability to shelter them in the event of an air raid. Once the danger of daytime raids had passed restrictions were eased, though Sunderland were still restricted to a capacity of 35,000 (set at half the total capacity) for the majority of the war.

Indeed, whilst the competitions continued Sunderland eventually entered the North Regional League in 1941-42 – the spectators who did attend got as much enjoyment from the guest player system, from seeing players such as Harry Potts and Stan Mortensen fill the red and white shirts on their return home on leave. For Stan in particular it was a dream he was never to fulfill in peacetime; Sunderland had rejected him as too small when he was a schoolboy with South Shields. Albert Stubbins, who worked as a draughtsman on Wearside during the war, turned out for Sunderland as a guest whilst on the official books of Newcastle. Another Magpie whom Sunderland supporters in later years would have been incredulous to see in a red-and-white shirt was Jackie Milburn, who failed to score on his two appearances for Sunderland.

Overall, Sunderland’s performances were erratic. Despite the occasional appearances of guest players such as the above the club, and indeed the North-East in general, could not find consistency. This was particularly so for Sunderland at home. Our best performance was in getting to the Final of the League War Cup in 1941-42, Wolves proving too strong for a Roker team that had scored 103 goals that season but kept few clean sheets.

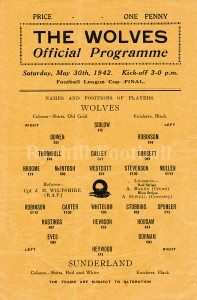

War Cup Final 1942 – official programme v Wolverhampton Wanderers

During the course of the conflict many players had, tragically, given their lives for their country, including former Sunderland players Jimmy Temple (killed on active service), and Percy Saunders, lost at sea following the invasion of Singapore in 1942. Outside-right John Lynas, trainer with Blackpool at the start of the war, was captured at Singapore and worked in a POW hospital in Thailand.

Future Sunderland players were also involved in the conflict, including Ken Chisholm as an RAF pilot and Billy Elliott as a Royal Navy AB seaman hunting U-boats.

When the war ended in 1945 time was too short to re-commence the Football League programme, the reasoning being in part that many footballers were still in the forces, particularly in the Far East.

The Football League North, which had previously been constituted on a two-part basis and combined with the League North Cup under rules which must have seemed logical at the time even if they make little sense over fifty years later, was reconstituted as a single 42-game league for the 1945-46 season. Sunderland finished 18th, losing over half their matches and conceding 83 goals.

The FA Cup attracted the greatest attention in season 1945-46, with ties being played over two legs. Sunderland disposed of Grimsby and Bury in the first two rounds, before going out to Birmingham despite winning the first leg 1-0 at Roker in front of a crowd of 44,820 who paid record receipts of £4631 2s. The second leg finished 3-1 to the Blues, who went on to the semi-final, going out to Derby at Maine Road in front of a record midweek crowd of 80,480. Cyril Brown, one of a handful of players to have played for Sunderland in the Cup but not the League, scored in every round that season.

The next season the Football League competition would restart with a vengeance, and the crowds would return everywhere in their droves. It was time for the post-war soccer boom.

On 7 May 1945 Germany surrendered unconditionally to Allied forces and the war in Europe had come to an end. It would be 4 more months before VJ Day, but on 2 September 1945 at 9.04am Japan surrendered to the USA on USS Missouri.

By the end of the conflict over 9m Jews had lost their lives, 2 out of every 3 in Europe, as part of Adolf Hitler’s final solution. The social consequences were of course felt by virtually every nation on the globe, but it was over and the world could start to rebuild its society. Everyone hoped and prayed that civilisation could once more become civilised again.

Winston Churchill the British Prime minister was determined that during the war the peoples lives at home would be as normalised as possible and he gave his official seal of approval to football of sorts continuing. In 1941 for example he attended an England v Scotland fixture with 7 of his cabinet ministers, and in 1944 both the King and field Marshall Montgomery, watched a similar game.

There were of course some interesting stories. Notts county used some 132 players during one of the war seasons, guesting was common. Bert Trautmann the famous German goalkeeper, was captured by the Allies, and ended up in a prisoner of war camp in England. He stayed on, rather than be repatriated and the rest as they say is history.

Humanity started to get back to normal…or as normal as it could ever now be…and that of course included football. Nearly 100 British professional footballers lost their lives during the wars. As players started to return to their clubs, they did so in the knowledge that some of their former team mates would not be joining them.

No facet of British life had been spared the horrors and tragedy of the conflict.

1945/46

The 1945/46 season was officially recognised by the Football Association only, the football League didn’t commence in earnest until 1946/47. However league competition of sorts did take place with an officially sanctioned football League North.

Our fist league game took place on 25 August 1945, against Sheffield Wednesday at Hillsborough. We would lose 3 v 6, but the score didn’t really matter…we were back in action. For the record it is worth noting the Sunderland team line up that day:

Haywood, Stelling, Eves, Lurie (Dundee), Lockie, Housam, Spuhler, Brown, Whitelum, Carter, Burbanks.

Raich Carter scored our first goal, then again, before Burbanks notched our third.

We were up and running.

For the return game at Roker Park, once more the majority of the fixtures were of the back to back variety, we won 1 v 0 in front of 22,300 fans. 5 consecutive defeats followed, and our next league victory didn’t arrive until the 17 October and a 4 v 0 success over Stoke City.

Bill Murray was still the Manager, a position he held from 1 April 1939 until 26 June 1957, only Bob Kyle served longer as boss of Sunderland AFC.

Funnily enough it was the perceived minnows of chesterfield who started off like a train and they inflicted 2 of our defeats, 0 v 3 at Roker and 0 v 5.

By the time of our second victory, over Barnsley at Roker manager Murray was already on the hunt for talent and travelled to Belfast on a scouting mission. The game against the Yorkshire side, watched by 14,000 spectators included a debut for the Silksworth Junior Hetherington, just 16 years old.

The success over Stoke City had Colonel Prior indicating that it was a good win for an All England XI, but one must confess I don’t like playing guest players. In an effort to gain some victories Manager Murray had invited players to play for Sunderland, and on this occasion it had the desired effect.

Our forward line in the 0 v 4 defeat at Goodison had an average age of only 18.

By the time we had played 12 games our record was pretty miserable and read; 3 wins, 9 losses, goals for 12, goals against 38.

Thompson, an 18 year old full back from Leaholme made a big impression in the 1 v 0, 3 November success over Bolton, and in the return game Johnny Mapson was finally back between the sticks. The game at Burnden Park was eventful as Whitelum gave Sunderland a first minute lead, Mapson saved a twice taken penalty, the Lancashire side equalised, before Burbanks converted a spot kick after fielding in the Wanderers goal was adjudged to have fouled Duns.

Tom Finney still starred for Preston and assisted then to a 1 v 1 draw at Deepdale. Leeds United found themselves 2 goals down to the red and whites at Elland Road, inside 17 minutes, but recovered to triumph 4 v 2, but we gained revenge in the return with a 5 v 1 thrashing of the Yorkshiremen.

We then played Manchester United and a win and a draw resulted. The main fact about the away fixture was that it was played at Maine Road, with Old Trafford out of commission due to bomb damage during the war.

Defeats by both Sheffield United at Roker, and Middlesbrough at Ayresome Park, meant that it was 5 January and therefore FA Cup time.

The first Cup Final after the war was won in 1946 by Derby County, who defeated Charlton Athletic 4 v 1. Raich Carter would famously be included in The Rams team having played his last game for Sunderland on 15 December 1945 in the 1 v 2 defeat by The Red Devils.

The FA cup was played on a 2 legged, home and away basis, with our first opponents being Grimsby Town. The first match at Blundell Park resulted in a 3 v 1 red and white win with Brown giving us the lead after 14 minutes. At Roker, in front of 19,500 people we finished the job off 2 v 1, and eased comfortably into the next phase.

It was bury who travelled to Wearside for the first game of the next round, and the Lancashire side eventually succumbed to Sunderland by 3 goals to one, setting up an interesting game at Gigg Lane. Although we lost 4 v 5 we progressed into the 5th round of the cup, after an extra time beauty by Burbanks sealed it.

The next round and Birmingham City saw 45,000 pack into Roker, Sunderland’s biggest crowd since before the war, and they witnessed a fine game, with duns scoring the only goal of the game, not long after The Blues Bodle had hit the bar. In the return we were defeated 1 v 3 and ended our interest in the first post war FA cup competition, when 3 second half goals in just 25 minutes crashed past Mapson.

By the beginning of February Sunderland had opened negotiations with Huddersfield Town for the services of Willie Watson, there international forward, and in fact the deal looked to have been going through in this month. However Watson was still in the Army based at Reading and so a date of 1 May was agreed.

Out of the FA Cup there was little to play for even though there were still 16 league games left. It was time to blood some youngsters.

The lad that made the biggest impression was a centre forward called Cyril Brown. Against Blackpool, Mortensen and all he came close twice and at Anfield in the company of the likes of Merseyside’s Liddell he stole the show in a 2 v 2 draw. He had arrived from Brentford but his stay wouldn’t last long. By the beginning of the next season he would be plying his trade with Notts County.

It was reported in the press that a flying Officer, formerly an amateur with spurs, and the son of a former Millwall player, would be signing for Carlisle United. His name; Ivor Broadis. Demobbed that year after 4 years in the RAF he would eventually sign for Sunderland in 1949.

Our league form never really improved and it was a mixture of wins and defeats until the end of the season, one that had no consistency about it.

Crowds at all grounds dwindled, and Roker witnessed attendance just above the 10,000 mark for some of the games. Some of course hit the heights, with the North East derby games always popular.

For example the game with Newcastle United on 20 April drew some 37,000 spectators, who saw a Burbanks goal, after only 4 minutes settle a tense affair. In the return at St James, United scored their 100th goal of the season in a 4 v 1 rout of the red and whites, with Milburn and Stubbins significantly scoring.

The 4 May game with Middlesbrough at Roker Park saw Willie Watson make his long awaited debut. It didn’t matter that he was in the side because we succumbed 0 v 1 to a Fenton goal after 20 minutes.

We just had time to lose at Roker Park to Darlington in the final of the Durham Professional cup before the season was up.

We had escaped the bottom 3 in the table, but only just. It didn’t really matter, that we had a poor season, football had resumed after the war and the football league programme could now begin in earnest.

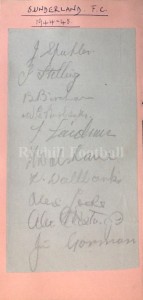

More action from the 1942 War Cup Final at Roker Park v Wolves.